Education has long served as one of the most prominent instruments of UK soft power, particularly across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). The British Council, Chevening Scholarships, and partnerships with elite regional institutions have historically projected a narrative of mutual learning and opportunity. But behind that narrative lies a critical truth: access alone does not guarantee equity. Today, UK education policy and aid are in urgent need of rethinking, especially when it comes to refugee learners, aid recipients, and marginalised youth across the region.

Refugee Access Isn’t Enough: Integration, Dignity, and Legal Security

UK policy discourse has framed scholarships for refugees as a hallmark of generosity. Initiatives like the University Sponsorship Model and targeted programmes such as the Refugee Education UK model demonstrate institutional awareness of barriers to higher education for displaced youth. However, the overwhelming focus on initial access hides a deeper issue: what happens after admission?

Refugee students in the UK continue to face significant challenges—language gaps, mental health burdens, financial precarity, and, most critically, immigration insecurity post-graduation. According to a report by Universities UK, many refugee students are left without clear routes to remain in the country legally after completing their degrees (Universities UK International, 2022). This undermines any claim to integration. Refugees are admitted, but not genuinely welcomed into the academic, social, or civic fabric of the institutions they attend.

Moreover, many institutions lack trauma-informed academic support and fail to include refugee voices in governance and curriculum design meaningfully. This mirrors broader issues in UK policy that prioritise optics over sustainability. A genuinely inclusive model would secure post-study protection pathways, integrate psychosocial and legal support into education planning, and treat refugee learners not as passive recipients of aid but as co-creators of knowledge.

UK Education Aid, Still Colonial in Form, If Not in Name

Beyond its borders, the UK continues to structure education aid to the MENA region through a donor-led lens. While funding for English-language and vocational training is abundant, it rarely supports regional knowledge systems, Arabic-language research, or refugee-led education. Most aid flows through British or international NGOs, sidelining local actors and reinforcing dependency. This top-down model undermines educational sovereignty and fosters fragile systems reliant on external support. Politically, this is short-sighted. Locally grounded education ecosystems reduce the need for prolonged aid and foster regional stability—directly benefiting UK interests. As displacement and conflict rise, instability in MENA increasingly impacts the UK through border pressures and global insecurity. Investing in decolonial curricula, Arabic-language journals, and refugee-led learning is not only equitable—it’s strategic. By co-creating solutions rather than exporting models, the UK can reduce future humanitarian costs, support migration management, and build more meaningful, respectful partnerships.

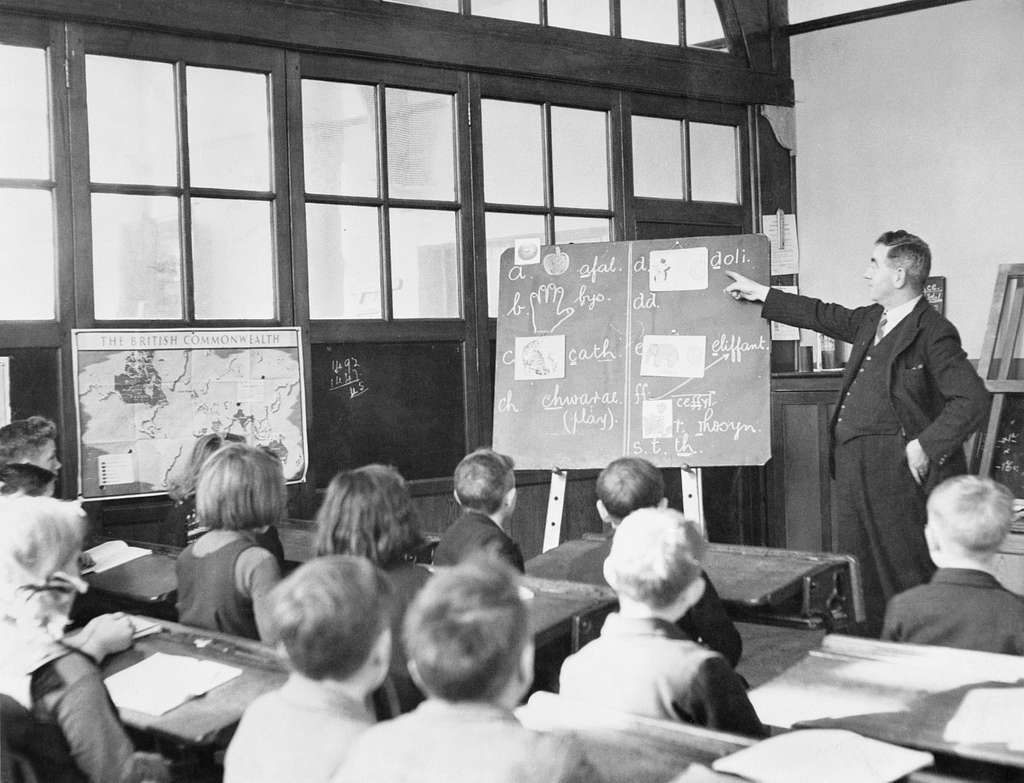

This model is not neutral. Scholars like Sultana (2019) argue that education aid often serves as a form of “pedagogical imperialism,” exporting Western epistemologies and marginalising indigenous forms of knowledge production. The UK’s aid infrastructure also demands that MENA youth adapt to British educational logic rather than co-constructing locally grounded, context-responsive models.

There is a need to reimagine UK aid as a platform for educational justice that funds decolonial curricula, supports Arabic-language research journals, and empowers refugee- and youth-led education spaces. The shift from technical capacity-building to political agency must be made explicit.

Mobility as a Right, not a Privilege: Rebuilding Regional Exchange

Another missing pillar of UK policy is investment in regional youth mobility within the MENA region. UK foreign policy, especially post-Brexit, has retreated from collaborative mobility platforms like Erasmus+, leaving a vacuum in regional exchange. While scholarships to study in the UK are still awarded, few resources are devoted to building mobility infrastructure between Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and North African countries.

This is a strategic error. Regional exchange—through joint academic programmes, digital learning partnerships, or research fellowships—is vital for civic participation, innovation, and peacebuilding; it also remaps relationships and reshapes regional agency. Yet UK education investments remain overly focused on unidirectional flow: bringing select students “to the UK” under restrictive visa terms rather than empowering regional collaboration.

Moreover, visa restrictions and border securitisation mean that stateless and displaced youth from places like Gaza, Western Sahara, or Syria are excluded entirely from exchange programmes. These are the very voices that should be at the centre of British educational efforts thical mobility infrastructure must include remote access pathways, co-designed regional initiatives, and South–South partnerships and fostering collaboration between young people across the region.”

From Education as Charity to Education as Solidarity

If the UK wants to remain relevant in global education diplomacy, it must shift from charity to solidarity. That means recognising refugees and MENA youth not just as vulnerable populations to serve, but as intellectual and political actors capable of transforming education systems.

It also means holding UK institutions accountable for reproducing exclusion. Education that uplifts must be locally rooted, co-produced, multilingual, and legally accessible. Anything else is a modern repackaging of colonial control.

As climate change, displacement, and inequality reshape global realities, the UK must remain a gatekeeper of privilege or become a partner in reimagining education for justice and liberation.

References

- British Council (2021). Next Generation MENA: Youth Voice in a Changing Region. https://www.britishcouncil.org/research-policy-insight/insight-articles/next-generation-mena

- Refugee Education UK. https://refugeeeducation.org.uk/

- Universities UK International (2022). Guidance for supporting displaced students. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/

- Sultana, F. (2019). Decolonizing Development Education and the Pursuit of Epistemic Justice. Comparative Education Review, 63(3), 315–336.