Earlier this week, Louis Theraux released his latest documentary, The Settlers. While the conflict in Palestine has not left public scrutiny, it had begun to retreat in the face of headlines about Donald Trump, European defence, and local council elections. Nonetheless, the public remains passionate about the issue. In a recent Question Time episode, one audience member asked “[Your heart is breaking for Israeli children,] why isn’t your heart breaking for the Palestinian children that are dying? Why is an Israeli life more valuable [to you] than a Palestinian life?”.

Heart-wrenching and frankly traumatising clips can be found across the internet of Israel’s response to Hamas’ attacks from October 2023. Amnesty International had already declared Israel’s actions as being consistent with apartheid but the violence unleashed since Hamas’ attacks has led the International Criminal Court to issue arrest warrants to Israeli leaders such as Benjamin Netanyahu for war crimes. Moreover, a range of public commentators – from Irish rap-group Kneecap to the United Nations Human Rights Committee – have argued that Israel’s violence constitutes genocide.

In the face of such atrocity, the UK has failed to shape or even influence events in the region. When two British MPs attempted to travel to Palestine’s West Bank, they were detained and refused entry to Israel before being returned to London. For a country that is currently rallying Europe to stand up for Ukraine’s sovereignty and that has historically taken action in Kosovo on the grounds of preventing crimes against humanity, its current reaction to Israel is nothing short of anaemic. In this piece, I want to explore why.

Context

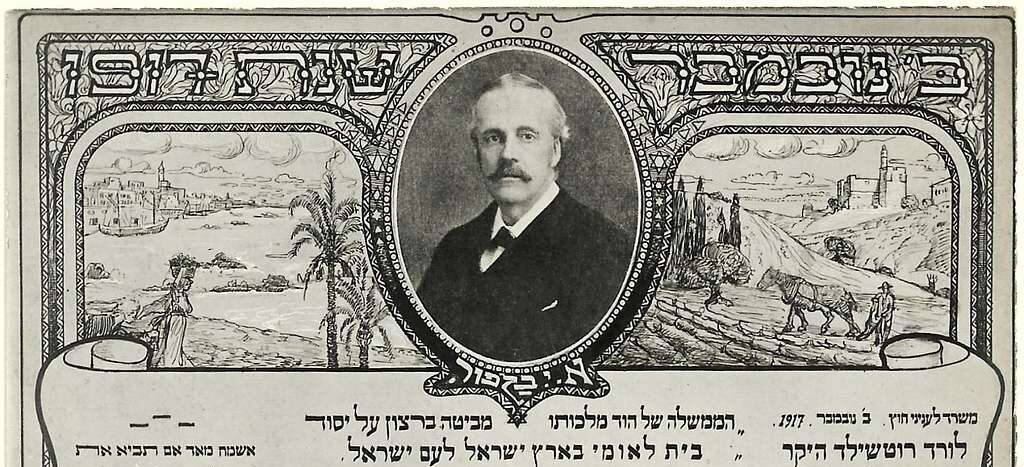

The UK has been involved with Israel-Palestine since before Israel’s conception. Having ruled the area under the British Mandate, Zionist terrorists fought to gain a space that Jews could call their own. Nationalist and anti-colonialist movements across the Middle East were beginning to rally as the Ottoman Empire failed to keep up with a burgeoning modernity. In 1917, the British government, represented by Arthur Balfour, issued a public statement in support of a “national home for the Jewish people”. At the time, the British were also supporting the Arab uprising with leaders like Lawrence of Arabia helping tribes to challenge the Ottomans and promising them Arab self-determination across the Middle East. This two-faced and conflicting policy has shaped British involvement in the region ever since.

This is to say that the UK has always, and will always have, a more nuanced approach to resolving conflict between Israel and Palestine. Unlike other actors and states that can sway one side or another, the UK must take responsibility for initiating this situation and as a result, take an active but collaborative approach to both states.

Interests and Values

“Therefore I say that it is a narrow policy to suppose that this country or that is to be marked out as the eternal ally or the perpetual enemy of England. We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”

– Lord Palmerston

States, ultimately, are driven by both values and interests. When we look to the UK’s lacking response in regards to Israel-Palestine, we have to assess what the UK wants to achieve, and what the UK can feasibly achieve while balancing other priorities. This is ultimately the separation between values and interests.

Values determines the destination a state aims for. Whether it’s universal human rights, free trade, or a paternal role as a heavenly kingdom, states – particularly powerful ones – have a vision for the world they want to build and the way they want to interact with the world. Values set the direction for states attempting to navigate an uncertain and dangerous world.

Interests, by contrast, are the actions – or reactions – a state must undertake in the present and imminent future. With conflicts closer to home, domestic challenges to manage, and potential virus-inducing shocks, states must also deal with what is in front of them. Interests are sometimes categorised into vital, critical, and general based on the severity of the situation. Where values are a compass setting the general direction, interests are the challenge of figuring out how to reach the destination without having to walk straight through a swamp.

An example of this might be seen with Turing’s cracking of the Enigma Code. Britain had discovered how to decipher German communications and were thus able to locate German U-boats threatening to sink convoys of civilians and food supplies. The value at stake was peace and the preservation of (British) life. Pursuing values, therefore, might have meant bombing all German U-boats to protect such civilians. Yet, had this course of action been taken, the Germans would have realised their Enigma Code had been cracked and would have developed a new means for encrypting messages – ultimately extending the war. Instead, lives were sacrificed to hide the revelation of German communications so that more important operations could be undertaken like D-Day, ultimately hastening the end of the war and preventing a further loss of (British) life.

In times of conflict, tough calls have to be made. The question is whether the British government has been making any of those calls or, even more worryingly, if they are able to.

Who are we more interested in?

Standing up for Palestine blatantly falls within the UK’s values. Ensuring Israel respects international law, allowing humanitarian aid to enter Gaza, a proportional military response to the October attacks are all points that are consistent with the world the UK aims to encourage. This is not just my argument either, it is government messaging too. Foreign Secretary David Lammy has made a point of publicly discussing Israel’s blockade of humanitarian aid as well as opposing Israel’s resumption of hostilities in March.

Clearly, the UK values an Israel-Palestine relationship in which there is no conflict – or if there is, then conflict that is proportional to the threat – and one in line with international law. So, is the lack of meaningful response to do with the UK’s interests?

On the one hand, the UK has already committed to supporting Ukraine while navigating its relationship with the US on top of domestic challenges brought on by economic and social insecurity. Nonetheless, there are several clear reasons as to why it is in the UK’s interests to more vigorously engage with the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Firstly, it has been widely argued by diplomats and political commentators such as Rory Stewart that Arab states and their populations are growing angry at the West’s inaction. Having witnessed the robust response for Ukraine on the basis of international law, why is it that Palestine does not deserve the same support? This sort of perspective puts pressure on Arab leaders to make – or not make – certain decisions regarding the West. It means that instead of being able to constructively and cooperatively work to deal with migration, improving trade, and international crime, the West is faced with a population that lacks any desire to engage with us.

More fundamentally, losing credibility for our values reframes how populations see us. Most people in the UK would not see ourselves as a colonial power but to populations that are watching us failing to challenge a state that they see to be colonial (Israel), it starts to seem like collusion. It means that when we take the stage at the UN to advocate for something like reducing the use of fossil fuels, other states assume the worst – that we are limiting the developing world’s ability to grow. A lack of credibility in our values means less reason for others to engage with our values – if even we don’t care about international law, why should they?

There is also the practical and imminent challenge of increased instability in the region with the Yemeni Houthis attacking shipping in the Red Sea, Iran taking aim at Israel, and Israel attacking Lebanon. The UK voted to not engage with Syria in the early-2010s and then faced the consequences of mass asylum seekers providing fuel to the far-right. Clearly, working to encourage stability in the region, building international credibility for our values, and demonstrating to millions across the Middle East that the UK is earnest about working constructively with Arabs is within our interests.

Bedridden Britain

Given that there are imminent, material, and moral reasons as to why the UK should be challenging Israel’s violence more vigorously, why is it not standing up for Palestine?

To my mind, there are three reasons.

The first is a generational issue. We have a generation of policymakers that fundamentally understand Israel as a victim and as a friendly state in a precarious environment. Raised by parents who fought the Nazis and having witnessed the various attacks launched against Israel in decades gone by, their perspective is one of quiet sympathy. Such a perspective makes it hard to thoroughly investigate the acts of war crimes, apartheid, and illegal colonial settlement that have characterised Israeli foreign policy in recent decades. It makes individual politicians reluctant to take on a confrontational stance as opposed to simply reigning in specific excesses.

Secondly, these same politicians are more likely to have climbed the greasy pole by dealing with local issues and local party politics. They themselves are unfamiliar with the nuances of Israel-Palestine as well as the broader Middle East which makes shaping public opinion even more daunting. Having to figure out where you stand, what that means in relation to your broader party, and how to communicate that effectively is Herculean. In recent decades, Brits have felt an itch that they ought to do something when it comes to problematic foreign affairs but have frequently failed to see the issues through. As an MP, having to communicate why we are doing what we are doing vis-à-vis Israel-Palestine, and why we need to do so much when other states in the region are themselves not as materially committed seems like a quick way to damage your rapport with your constituents – especially if you are a new MP. That is the situation now, let alone if events were to become more confrontational and required more invested involvement to achieve stated interests.

Finally, and this is the closest I can find to there being an actual interest behind not challenging Israel, is the US. Specifically, our relationship with it. In 1956, Egypt attempted to nationalise the Suez Canal. The UK, France, and (ironically) Israel banded together to launch a military operation to prevent this. The outcome was the US forcing the trilateral attempt to come to an end. The UK has since maintained a consistent strategy of avoiding contrasting policies with the US that draw confrontation. The US also, for a variety of reasons, maintains incredibly strong ties with Israel. Challenging Israel might, to some, risk challenging the US position in the Middle East with ramifications for our relationship with the US. Given recent developments in this ‘special relationship’, perhaps it is time to reconsider our hesitancy.

Combine these three points and you are left with a political class that is not sure about the intricacies of the issue, is hesitant to investigate further, and risk-averse in the case of frustrating the US. When there are problems closer to home that are more easily understandable, and more easily resolved, it is no wonder that our politicians lack the conviction needed to shape public opinion and challenge Israel. Yet, as Burke of all people reminds us, the only thing required for the triumph of evil is for good people to do nothing.

Final Thoughts

Frankly, I can see why other countries and people see the UK’s lack of conviction for standing up for Palestinians as evidence that we are, in fact, a colonialist country that has attempted some rebranding. We rally Europe behind Ukraine yet offer nothing but platitudes for Palestine. The optics that, when the die is cast, we ultimately enabled an oppressor instead of siding with the oppressed is hard to ignore. But to me, a more convincing – and in some ways more worrying – interpretation is that British politics has become stagnant, anaemic, and timid. Bismarck said that the issues of his day will be solved by iron and steel – real commitments, not just words. But can Britain handle the heat of the smelter anymore?